|

Nakai Toh - My Days with the Finest People on God's Green Earthby Walter Gibson |

|---|

What follows is an account of my years as a trader on the Navajo Reservation in northern Arizona. These years began in 1923 and lasted until the forties. They were good years though lonely sometimes and isolated, but during this time I learned to appreciate the Navajo people and it is that, that made them worthwhile and rewarding.

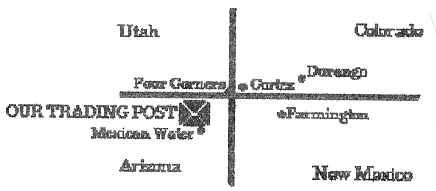

I was twelve years old the first time I journeyed from Farmington, New Mexico, to the trading post at Mexican Water, Arizona. My father had been running a store in Flora Vista, New Mexico, when he heard a trading post there was for sale. This was a mysterious and challenging world for a young man, something I will remember all my life. My older brother drove the old model T the one hundred one miles across the rough rocky trail that most folks today would not consider a road. It was slow going and took us from eight in the morning until sundown. I began to think they were taking me to the end of the world to dump me.

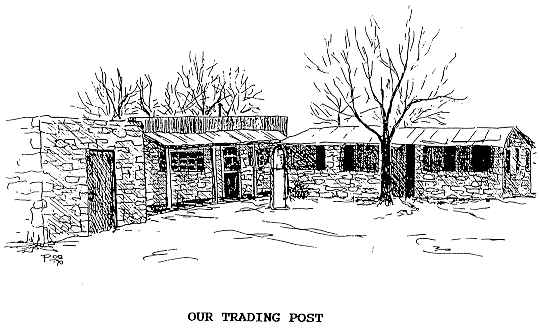

The Post was built around the turn of the century. The Bureau of Indian Affairs classed it as a trading post. Actually it was just an old fashioned country store, located in one of the most remote places in Arizona. We had to be self sufficient for there was no such thing as electricity, running water or plumbing and during the first three or four years we had no radio, and would probably see another white man only about once a week.

The building, constructed of native sandstone, had walls about eighteen inches thick. Inside there were shelves around the walls and a counter, built mostly from the crates that Arbuckle Brothers used for shipping their Ariosa Coffee. In fact I have often wondered if any of the posts around these parts would have had any counters or shelves if Arbuckles had not used these wood crates.

Like all the others, our Post had a section in the middle which we called the "bullpen". Here our Navajo customers would mill around and visit with their neighbors before doing their shopping. Out in front was a hitching post where they tied up their horses. Usually the rail had a fresh goat skin draped across it to dry.

Although the post was not very large we had a little bit of everything the Navajos needed, as most of them were pretty self sufficient. Some families lived a considerable distance from where we were and would come into shop only once in sixty or ninety days. Then they would stock up on coffee, sugar, salt, tobacco, flour and canned goods. The best seller was canned tomatoes but they would also purchase canned fruits and corned beef. Once in a while the women would buy cheese, dry beans and rice. The grown folks were as bad as the children when it came to candy, gum, cookies and Cracker Jacks. We also carried a supply of hardware, dry goods, and stock feed. Women liked sateen for skirts and velveteen for blouses and would select enough for a new outfit from the three or four colors we carried. None of this material could be cut with scissors and we had to rip it from the bolt. Somehow, ripping made for straighter pieces.

For the men and boys we carried all sizes of trousers and shirts, mostly in denim. Of course, there were western hats and shoes for all ages. It was interesting that size eight was the largest shoe we carried. The Navajo people seem to have small feet. When parents bought shoes for the children that were not with them they would bring a string with knots on it indicating the size needed. We of course always assured them that if the shoes didn't fit they could come back for a replacement.

Trading during these times was strictly that. We traded goods, food stuffs, and clothing for wool, lambs, hides, rugs and furs. Ninety-nine percent of our business was transacted without a single penny being involved. From the other side of the counter the traders would purchase blankets, goat skins, sheep pelts, horses, cow hides, rugs, and saddle blankets the year around. In the spring when our customers sheared their sheep we bought the wool. Then in the fall we bought the lambs and drove them a hundred miles to the railroad for shipment to market. Here again no money changed hands. We kept a paper showing each transaction and hoped that when the wool and lambs, along with the other items, were sold at market the credit would be cleared making more credit available. If for some reason the transactions did not clear the balance we never refused to carry the customers on until better times and they could pay up the debt.

The Navajo Trader was more than a store keeper. We helped build caskets and bury the dead. Many times we arose in the middle of the night to give needed supplies to a father for a sick child. Rarely did we ever get to town without one or more Navajos needing medical aid at the Indian Service Hospital seventy miles away. Our customers came to us for counseling on their financial affairs and we often helped them to acquire better grades of livestock. There were times when we drove day or night for the police or medical help in cases of emergencies. And we were even guilty of practicing medicine without a license. For us the handclasp and quiet greetings from these wonderful customers and friends of ours made up for all the work and expense.

My father bought a new Model T with an auxiliary transmission called a jumbo. The gas tank was under the seat and since there was no such thing as a fuel pump when the gas was low it would not flow into the carburetor when you were on a steep grade or hill. This caused trouble when we drove into Farmington for supplies. On a number of hills it was possible to turn the car around and back up, but on Old Blue Hill this was too risky. The road was narrow and had too many sharp turns and blind spots so backing was not realistic. Dad concocted a system to whip that old hill. He soldered a tire valve stem to an extra gas tank cap, and when we reached the foot of the hill we stopped and using a tire pump pumped enough pressure into the gas tank to force it into the carburetor.

Dad solved another problem too. Sometimes we would get stuck going up a hill. If you didn't have a companion with you to put a rock behind the wheel to roll back on, you would have to go all the way to the bottom of the hill and start over. With the rock in place the driver could race the motor and let the clutch out, or in the case of the model T shove your left foot down hard on the low pedal and move, hopefully upgrade a few feet until you reached the top. When you were alone you had to hit the brake and the clutch both at once, race the motor, let up on the brake just as you released the clutch and try to gain ground. Normally, the car starts to roll down hill and your power is consumed in just stopping the backward roll. Well, my dad came up with another lulu of a gadget. He got a piece of six by six lumber about eighteen inches long and attached it to drag behind the wheel. At the foot of all the hills that were questionable we would stop at the bottom, take the six by six out and let it drag behind us until it stopped the car, then proceeded as if it were a rock.

Most days were the same; quiet and often lonely. However, when an event occurs so different from the usual it is always a fresh memory. Keep in mind that often a week or more would go by between cars or trucks at the Post. Even then, it would usually be only a neighbor trader. Well one day, three young boys came running into the Post and one, who had been to school said to me, "Here comes a big tall man--maybe it's Jesus Christ!"

He no sooner said that when here came a very large man with a beard an old cloak of some kind and burlap wrappings for shoes. He asked for some food stuffs. We offered him anything he desired; putting cans of fruit and tomatoes on the counter for him. He said no they were too heavy to carry. All he wanted was a few pounds of flour, stating that when he mixed it with water it was all that he needed. "Besides", he added, "all the people here are so nice and kind. Whenever I get to their homes, there will be food and coffee laid out for me. The people are, however, very timid and no one is ever there to greet me."

After that, the man the Navajo boy thought was Jesus, left and continued on foot toward Utah. Later those who had heard of him told me that the people were scared and ran and hid when he showed up. They were not timid, as he thought. It was an eerie occasion and once in a while, in thinking back, I get to wondering if maybe, just maybe, the young Navajo boy was right in his first impression.

******

Used by permission of the Grand Canyon Pioneers Society.

|

|

|---|

|

|---|