|

|---|

Summer 1999 |

The following article is an excerpt taken from the Summer 1999 issue of the Colorado Plateau Advocate,

a publication of the GRAND CANYON TRUST.

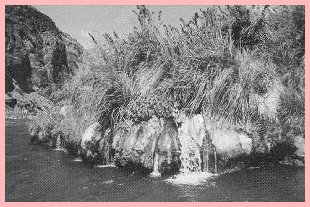

Lava Falls Well, Grand Canyon National Park Jeff A. Sorensen |

For millennia, the Greater Grand Canyon region was sparsely inhabited, the lack of available water being a serious limit to growth. After settlement by Anglo-Europeans, and the consequent advent of surface water impoundment and deep well technologies, this historical limit to growth was shattered.

Now, with a burgeoning population over 100,000 in 1990, and projected to more than double in the next thirty to forty years, the water limit appears to be raising its head again. The Arizona Department of Water Resources (DWR), has concluded that water supply needs in the Greater Grand Canyon (GGC) will double right along with the population. Given the growth and demand projections, the obvious question arises: where will the needed water come from?

To explore answers to this question, DWR has recently organized the North Central Arizona Regional Water Study. Participants in the study include the Navajo and Havasupai tribes, the cities of Flagstaff, Williams, Page and Tusayan, Grand Canyon National Park, Kaibab National Forest, and Coconino County.

The Trust has been following this process and we are quite concerned. So far, little serious attention has been paid to the more sustainable options of limiting growth and utilizing serious water conservation technologies. Instead, DWR has focused great attention on a proposed pipeline, dubbed the Western Navajo Pipeline. This pipeline would run south from Lake Powell near Page to Cameron, with one arm splitting to the west, delivering water to the Grand Canyon, Tusayan, Valle, Williams, and the other arm continuing south to Flagstaff.

While the proposal is still in the early planning stages, and details remain sketchy, Grand Canyon Trust believes that such a pipeline would facilitate unwanted, explosive, and environmentally devastating growth in the region. For example, if water was made available to the vast area between Williams and Grand Canyon National Park, mushrooming wildcat subdivisions could easily sprawl throughout the scenic, rural countryside south of Grand Canyon.

At the same time, the option of increasing the GGC's current water dependence on deep aquifer mining is also very problematic. On the Coconino Plateau, current studies indicate that such pumping, already occurring in Tusayan and Valle, has great potential to negatively impact the Grand Canyon's south rims fragile seeps and springs.

Similar deep aquifer mining near Flagstaff is less well-studied in terms of its potential impacts to springs in the Mogollon Rim, springs that feed such critical habitats as Oak Creek and Sycamore. Creek, to name just two. Although covering a small percentage of the GGC's land area, the riparian zones dependent on aquifer-fed springs play an essential role in sustaining diverse ecosystems in the region.

Because of the lack of apparent environmentally-sound water supply options, the Trust believes we must focus greater attention on sustainable alternatives for creating a water supply, including water conservation, water efficiency and water harvesting techniques. The potential is there: the Rocky Mountain Institute has projected savings up to 50% with the use of best available water conservation technologies. Such reduction in water demand would allow for expected growth without need for development of additional water supplies.

And, of course, growth management and controls

must absolutely be part of the overall equation in

the region. Real environmental limits exist, and

breaching them from lack of care and foresight will

ultimately come back to haunt us and harm those that follow.

![]()

-Nikolai Ramsey

|

|

|---|

|

|---|