|

Sunday, August 10, 1997

By the end of this day we will have traveled through nearly 300 million years of geologic time. We had started out in the Triassic Period in the Moenkopi Formation at the boat ramp at Lees Ferry, entered the Permian Period at the level of the Kaibab Limestone just two tenths of a mile down the river, the Toroweap Formation a mile later, the Cocnino Sandstone cliffs 4 miles down, (just before we went beneath the Navajo Bridges) the Hermit Shale 2 miles farther on, and the Pennsylvanian Period with the complicated levels of the Supai formation at Soap Creek 11 miles down. Next we entered the Mississippian Period when we encountered the Redwall limestone just before we got to Indian Dick, and then we came to the Cambrian Period with the appearance of the gray Muav Limestone, (530 million years old) about a mile below Redwall Cavern. We didn't see the more recent layers of the Temple Butte Limestone of the Devonian Period, (370 million yeas old) until we got to the area between Tatahatso Wash and the Marble Canyon dam site, (mile 37 to mile 39) because here in the eastern end of the Grand Canyon region the only remains of this formation are the "fossilized" remains of old river channels. Apparently these Devonian rivers that flowed through the Muav on their way to the ancient sea eons ago silted up. Then the material became compressed, and what we now see are "lenses" of Temple Butte limestone in between the Muav below and the Redwall above. In the western end of the Canyon, where the deposits were beyond the ancient shores of the continent the Temple Butte is a thousand feet thick, and forms massive cliffs.

On our way this Sunday we would see the relatively soft mudstone and shale layers of the Bright Angel shale slowly rise up from the river level about 2 miles up from Nankoweap. This Layer of the so-called Tonto Group, (which group is composed of the Muav, the Bright Angel and the Tapeats Sandstone below) has been dated at about 540 million years old.

The reports that I have read speak with such authority on the age of these layers, that for many years I accepted the figures as reasonably accurate. Much to my surprise, I have recently learned that the age of the Tapeats layer is variously measured at 0.7 to 1.7 billion years, depending upon which element is used to measure the radioactive decay. Let's see now, our geologists have measured the years of that layer to within plus or minus a billion? - ??? Not as exact a science as I had been led to believe in my student days. Oh well. Anyhow this stuff is pretty old no matter how you look at it.

Those of us that wanted to take the hike, (read climb) up the old Eminence Trail this morning arose early, and gathered around Factor before breakfast for instructions. We were to take the hike in the cool of the early morning while the cliff we would be climbing would be in the shade. In order to get up and back before the sun hit us with its full heat we would have to start immediately, - before breakfast.

Since it had rained off and on all night, I was glad for the delay in packing up. It would give my tent time to dry out. I hate packing a wet tent.

Nancy Brian didn't have much to say about the trail we were about to take. She simply tells us that the Eminence Fault crosses the river here, and that an unmaintained trail follows the fault to the rim. According to Factor it is probably an old Indian trail that was used centuries ago. There is one thing about this information that is true. It is certainly unmaintained.

- VIEW DOWNSTREAM FROM UP ON THE EMINENCE TRAIL - VIEW DOWNSTREAM FROM UP ON THE EMINENCE TRAIL

The climb up was not too bad. My main problem, as it always is when I go on one of these guided hikes, is convincing the young guides that there is nothing wrong with my heart or my lungs, and that I don't need to take all of those rests. I can understand why they think what they do. They see this old geezer hobbling along with a walking stick, and naturally are a little concerned. My problem is not in going up. It is in coming back down. That's where my vertigo makes things difficult, and I have to be extremely careful.

The top of the Redwall, our destination, was something over 700 feet up from the river here, and we had excellent views of our camp below and to our left, President Harding Rapids a little to our right, and Point Hansbrough across the canyon in front of us. We took some pictures, which probably wouldn't convey the feeling that we experienced. They almost never do, but we keep on taking them anyway.

- BILL AT TOP OF REDWALL, PRESIDENT HARDING RAPIDS FAR BELOW - BILL AT TOP OF REDWALL, PRESIDENT HARDING RAPIDS FAR BELOW

Bill and I had a good laugh at how puny the rapids of President Harding looked to us from way up on the top of the Redwall cliff.

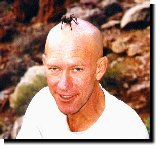

On our way back down Factor entertained us by putting a tarantula that he had found in the rocks on top of his shaved head. We got a good shot of that to remember him by.

- FACTOR WITH SPIDER ON HEAD - FACTOR WITH SPIDER ON HEAD

Then I entertained Factor by staggering from rock to rock, sliding from one drop off to the next, and clattering my cane to keep my balance in tight places, as we stumbled down the trail. This was pretty hard on his heart, but he held up just fine. We made it without any serious difficulty, and were back for breakfast by 10:00 a.m..

With the late breakfast our tents had thoroughly dried out, and packing was no problem.

Paddling down the river was OK, but wet. I was glad to have my pile outfit on under my foul weather gear, because shortly after we started the rains began again. At first the showers were intermittent, but soon they were constant. Within an hour we were rowing through intermittent thunderstorms with a steady rain in between.

Matthew and Scott Smith spent some time in the kayak, then Tim Chizak took over, and finally Matthew had enough. He got out and Scott got back in. I thought that those guys would freeze to death in the that little thing, but they told me that the exercise of paddling it kept them warm.

Six miles down from our previous night's camp we noticed the appearance of the Bright Angel Shale, first on the left bank, then on the right. A half mile or so upstream from Nankoweap Creek we noticed its delta that had been caused by a huge land and rock slide thousands of years ago. There is driftwood that was found on the floor of Stanton's Cave that was clearly washed in there by a flood, and that has been dated to 45,000 years ago. It is thought that the massive slide of Nankoweap probably dammed up the river, creating a huge lake behind it and flooding the cave that is 140 feet above the river and 20 miles upstream.

A little below the rapids of Nankoweap, about a mile from the granaries, we pulled in for lunch. It took the crew, with a little help from us passengers, (following instructions) a surprisingly short time to set up a good sized picnic shelter. Life in the rain on the river was a lot more tolerable under a shelter, and a good shot of whiskey provided by Don Streetman made it more tolerable still. Don is a friend of Diane Allen, who is one of Clyde Philbrick's daughters. Clyde and his family and friends made up half of our group.

Drying out under the shelter, and getting some good, hot vegetable soup in us, brought most of our shivering under control. We stood around a while, swapping yarns, telling lies, and generally making the best of a damp situation until it became obvious that all this rain, lightning and thunder was going to continue for a long, long time.

Right where we were, high above river level, and far removed from any area where an unexpected flood could hit us, and well away from a cliff where falling rocks and debris might be a problem was as good a place as could be found in the canyon to set up camp in weather like this, so it was decided to stay where we were. The old Indians thought that it was a good spot too.

There is a lot of evidence that this area has been occupied by prehistoric Indians who farmed the land that was created by the massive, ancient land slide. In addition to the granaries that everyone knows about there are foundations of buildings around the mouth of Nankoweap Creek, and there are other granaries that Bill and I saw high on the cliff on the south side of Nankoweap Canyon when we were here in 1993.

Dellenbaugh reports that Major Powell named the canyon for the echo that he could hear there. Nankoweap is a Paiute word meaning singing or echo.

The Nankoweap trail was originally constructed, as usual, by improving an old Indian trail. This was done by Powell's 1882-83 expedition in order to make it possible for the geologist Charles Doolittle Walcott to bring horses and equipment down along the canyon so that he could take samples and study the rock layers. He published his findings in a series of scientific papers, became well known, and in 1894 was made director of the US Geological Survey when Powell retired.

Nancy Brian mentioned that there is another story as to how Nankoweap got its name. Ninkuipi is a Paiute word meaning Indians or people killed, and they called this canyon Ninkuipi in honor of the Paiutes that were killed at Big Saddle by marauding Apaches. A battle between Paiutes and Apaches is known to have taken place at Big Saddle, and there is a report of it by an Indian named Johnny on file at the Grand Canyon

Once again, it's take your pick as to which story you think is more credible.

Let's get back from my digression.

I am constantly amazed at how well these river runners are able to adapt to difficult situations. Roger Dale called for the tents, which were packed in waterproof bags. The bags were opened, and the self standing tents assembled and set up under the shelter. That way the insides of the tents were nice and dry when they were carried out and set down in whatever area the camper selected.

I, to my great regret, had brought my own (non self standing) tent. With a break in the storm I quickly laid out my tent, but before I could get the waterproof fly over the top a terrific thunderclap boomed, and an equally terrific down pour followed. By the time my waterproof fly was in place my tent was full of water. That's when I learned that the good watertight floor and sides of the tent that were so fine for keeping ground water out, - are also fine for holding rain water in.

Grabbing one of the big sponges designed for bailing out the dories, I mopped, mopped and mopped some more. I got all of the water out, but everything inside was soaking wet. I was not looking forward to spending a night in that thing.

Factor organized a hike up to the granaries that were made famous by Colin Fletcher in his book, "The Man Who Walked Through Time." This was Fletcher's last camp on his hike from the Havasu Canyon to Point Imperial. He actually spent the night up there in the granaries. It was Fletcher's opinion that the structure was a home, and that people lived up there. He may be right, but the general thinking today is that the building was for food storage, and not living quarters.

Since Matthew didn't want to take the hike, and since both Bill and I had been there previously, and had a lot of pictures of us up there, plus the fact that it was raining and so foggy that from where we were you couldn't even see the cliff where the granaries were located, we didn't go.

After another delicious supper by Dennise and Nichol Corbo, with lots of help from Ote Dale, her daughter Alissa, and Rhonda Barbierri, Roger brought out a lot of folding chairs for us to sit on. (Where in the world do these people keep all of this stuff?) We were then entertained by Mike Meade, of Marina del Mar, CA, who regaled us with a whole lot of baa-a-aad jokes. They were so bad that after a while they got to be funny.

At last it was time to turn in. Without a doubt that night was the most miserable night that I have ever spent. It wasn't being cold that bothered me, because my pile outfit kept me warm. It was being wet. I was soaked to the skin - all over. At first my feet were a little cold inside my wet socks, but putting a garbage bag over them solved that problem. Believe it or not, I did sleep a little. When you get tired enough, you can sleep through almost anything. But I didn't sleep much, and during my waking periods I lay their listening to the pelting rain. I had the feeling that it would never end, that I would spend the rest of my life in the rain.

- PICTURE OF RAINY RIVER AT NANKOWEAP - PICTURE OF RAINY RIVER AT NANKOWEAP

|