|

DAY 3. TUESDAY, AUGUST 13, 2002

Tuesday dawned bright and clear. We were up, having coffee and stirring

around by a little after 6, and had an early breakfast of scrambled eggs,

hashbrowns, cut fruit, biscuits with jelly or jam, juice and more coffee at

6:45 am. Surprisingly, even though we got an early start nobody suggested

that we take a climb up into the well known cave of nautiloid canyon. On

previous trips this had been a fascinating place where it's possible to view

the fossilized remains of prehistoric nautiloid creatures that are distant

relatives of families of the squid and octopus.

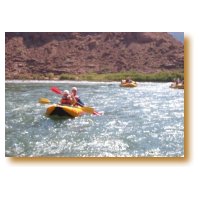

Cruising down reasonably calm water below 36 Mile Rapid, the crew made a

couple of inlflatable kayaks available to some of the adventurous passengers.

|

Note how clear the water is in 2002.

|

|

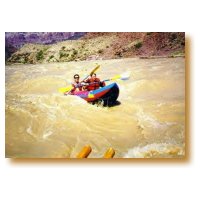

Note how muddy the water was in 1997. What a contrast!

|

As we made our way down the calm waters of mile 39 and 40 we noticed the

holes that had been drilled into the canyon walls in preparation for the

construction of Marble Canyon dam. This dam was fortunately blocked by David

Brower, executive director of the Sierra Club. He overcame the strong

influence of Floyd Dominy, commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, who

(supported by Senator Carl Hayden) in 1964 began pushing for dams just below

mile 39 in Marble Canyon and near mile 228 in the Grand Canyon. The Marble

Canyon Dam, and the Hualapai or Bridge Canyon Dam very nearly became a

reality. Brower won over a large number of voters by publishing his views in

the Washington Post, the New York Times, the Los Angeles times, and the San

Francisco Chronicle. When the Bureau of Reclamation argued that the dams

would improve the Grand Canyon by making it possible for boaters to get into

side canyons, and closer to the cliffs, Brower responded with his famous

question, "Should we also flood the Sistine Chapel so tourists can get nearer

the ceiling?" The battle is not yet over. The Hualapai Indian Tribe is still

agitating to have the Bridge Canyon Dam built along with a projected casino

in order to attract tourist trade to its reservation.

Gliding past Buck Farm Canyon`and Bert's Canyon we prepared to enter the

first significant test of the day, President Harding Rapid.

Albert (Bert) Loper, the Grand Old Man of the Canyon, was just short of his

80th birthday when he died while rowing 24.5 Mile Rapid in 1949. It is

generally thought that he died of a heart attack, and generally thought that

this was the way he wanted to die. His boat was found lodged on a rock bar

immediately upstream from this unnamed canyon, at mile 41.25, so it was given

the name "Bert's Canyon."

Five years ago Bill and I had successfully run President Harding in a kayak.

It had been a lot of fun. This year two kayaks also ran it with success, and

it was even more fun, because it was a warm and sunny day with almost crystal

clear water. This was a marked improvement over the brown, muddy turbulence

and cold blowing rain off 1997.

Claude S. Birdsey, chief of the USGS 1923 Survey Expedition named this rapid

for President Harding while the group was camped at this site on August 10.

By radio Birdseye learned that August 10 was the date set aside as a memorial

day to President Harding, who had been assassinated on August 2. Therefore

Boulder Rapid was renamed in Harding's honor.

We continued on beyond President Harding Rapid and the grand hairpin turn

around Point Hansbrough. This point was named by Robert Brewster Stanton for

Peter Hansbrough, one of Stanton's boatmen who had drowned at 25 Mile Rapid

in 1889. That was the expedition that had to be absndoned, with Stanton

caching his boat and supplies in Stanton's Cave. In 1990, on his second, and

successful, attempt, Stanton had found Handbrough's body (easily recognizable

by the clothing) washed ashore at this point.

|

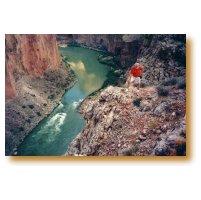

This is a view of President Harding Rapid from the top of the Eminance Break.

Point Hansbrough is on the opposite side of the river.

|

Two miles down from Point Hansbrough we came to Saddle Canyon, where we stop

to give those of us who are idiots the chance to hike in the heat up the

canyon. In spite of Rob's adequate warnings, some of our hardier members,

including Phil Roberts accept the challenge. Us smarter ones rested in shade

until they returned for lunch.

The remainder of the afternoon was spent in a leasurely cruise down the

placid waters of the river to Nankoweap Rapid at mile 52.

About 2 miles upstream from the Nankoweap Creek delta we cruised through a

stretch of river with nice campsites on either shore, and when we could see

through the tamarisk trees we were able to notice the relatively soft

mudstone and shale layers of Bright Angel Shale that was appearing at river

level. This layer of rock is the middle layer of the Tonto Group. It is so

soft and crumbly that it is easily eroded, and as it erodes it washes away

back under the harder and stronger layers of Muav and Redwall above it.

Having been undercut, huge chunks of unsupported, heavy Redwall break off,

and roll off down into the canyon. This leaves a broader and broader section

of exposed Bright Angel Shale with a receding cliff of Redwall or Muav and

Redwall above it, and this is how geologists explain the development of the

broad Tonto Platform that lies below the massive Redwall and Muav cliffs and

above the 300 or so foot Tapeats Sandstone cliffs.

As mentioned before these three layers, the Muav Limestone, the Bright Angel

Shale and the Tapeats Sandstone make up the 540 million year old Tonto Group.

By the way, the pretty tamarisk trees, through which we observed the rising

layers of Bright angel Shale, are not native to the Canyon. However, they

have become ubiquitous in the 50 years since they were introduced.. My

friend, Jimmie Davis says that ubiquitous means "They are all over the damned

place."

Tamarisks, native to the Middle East and sections of China, also known as

Salt Cedars. The were introduced into North America in the 1850's, because

botanists had noted that this hardy species would thrive almost anywhere and

in almost any kind of soil. They were brought over here for landscaping and

erosion control. In the Southwest they were planted primarily for erosion

control. Unfortunately they soon got out of control.

Initially it was thought that the introduction of tamarisks would be highly

beneficial for many reasons. For example, agriculturalists were aware of the

writings of Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) one of the foremost figures in

herbal medicine for his time. In his book, The Complete Herbal, he wrote, "A

gallant Saturnine herb it is." and pointed out a number of therapeutic uses.

( I get a kick out of this.)

"The leaves, young twigs, bark and/or roots, when boiled in wine produced a

drink that would, stay "…the bleeding of the hæmorrhodical veins," …

excessive menstrual flow, "…jaundice, cholic and spitting up blood,…" It

would also either cure, or reduce the effect of, "… the biting of all

venomous serpents, except the asp;…" This same medicine, if applied

topically, was, "…very powerful against the hardness of the spleen, and the

tooth-ache, pains in the ears, red and watering eyes." Now if you took the

same "decoction" and added some honey, (how much honey was not recorded) he

said that it, "…is good to stay gangrenes and fretting ulcers, and to wash

those that are subject to nits and lice." He goes on to tell us that,

"Alpinus and Veslingius affirm, That the Egyptians do with good success use

the wood of it to cure the French disease, as others do with lignum vitæ or

guiacum; and give it also to those who have the leprosy, scabs, ulcers, or

the like." Since the ashes of burned Tamerisk, "…quickly heal blisters raised

by burnings or scaldings."and "… helps the dropsy, arising from the hardness

of the spleen,…"it is best "…to drink out of cups made of the wood … for

splenetic persons." Oh, and "It is also helpful for melancholy, and the black

jaundice that arise thereof."

Soon it was discovered that these trees consumed a prodigious amount of

water. A mature, large tamarisk is capable of transpiring up to 1100 liters

of water every 24 hours. Small streams have been sucked dry by these pests.

Then other problems became evident. We learned that for good reason this tree

is also known as the Salt Cedar. It can grow in brackish and other mineral

water. It is able to do this because it has the unique capability of

purifying water for its sap by concentrating minerals in it's leaf tips. It

does this everywhere it grows. When it drops its leaves, and the leaves

decay in the soil, they don't enrich the soil as the leaves of other plants

do, but they ruin the soil by making it more salty. As the years go by other

plants find it harder and harder to live in the progressively more

mineralized and salty soil created by the tamarisks. Meanwhile the hardy

tamarisks continue to thrive. Besides all of this, the salinity of the leaves

makes them unpalatable to insects and, so the trees don't provide a very good

habitat for riparian life. Because of this characteristic they have

virtually no enemies to keep them in check.

Each Tamarisk produces up to 600,000 seeds a year; seeds that are blown on

the wind to start new plants. In addition new trees start from shoots

sprouting up from roots of old trees. When conservationists try to clear an

area by cutting them down, often many new shoots sprout up from rootlets left

in the ground, and the end result is an even more dense growth of tamarisks.

So now you know why for nearly half a century agricultural experts have been

trying to find a way to curb the spread of these pesky and stubborn plants.

So far their best efforts have met with a resounding failure.

As we rowed through the reasonably gentle Nankoweap Rapid around the delta

that was created by the huge landslide thousands of years ago we noticed that

there was plenty of camping room on shore, and plenty of space for our boats

on the bank south of the delta. A gigantic earthquake, by the way, had

caused such a landslide that a huge natural dam had been born, creating a

lake that had backed waters all the way back up, and into Stanton's Cave.

Since that time the river has overflowed the earthen dam, cutting a new

channel that arcs to the east side of the river. This is what has formed the

curve in the river and the Nankoweap Rapids.

Please note that Bill Huggins takes exception to my comment that the

Nankoweap Rapids are "reasonably gentle." Billie Prosser, his skipper for

the day, had traded places with him some time earlier in the afternoon,

allowing him to experience handling the oars of the suddenly, to Bill, big

and unwieldy raft. As they approached Nankoweap she continued to enjoy

relaxing while he rowed. He says he made it through the rapids, just barely

missing a big rock, and without spinning around or any one of a number of

things that he quickly realized could have gone wrong. It was much more

difficult, and required a lot more energy than he had realized. I stand

corrected. "Reasonably gentle" as descriptive of rapids in the Canyon

depends on where you are seated, and what your responsibilities are.

|

Here Bill is back and relaxing as

a passenger the day after his heroic oarsmanship through Nankoweap.

|

|

Bill rowing Scotty's boat in calm water the first day. This was a shake down for his run through Nankoweap Rapids.

|

We had the boats securely tied, and all of our gear unloaded in plenty of

time to select sleeping quareters, and still have time for leasurely

activities. Many of us hiked the relatively easy trail up to the famous

Anasazi Granaries. With my vertigo, knowing that I would have a good deal of

difficulty climbing back down, I stopped about half way up, and took some

pictures. This was just about the prettiest campsite of the entire trip.

|

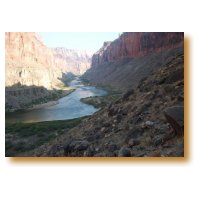

Marble Canyon looking south from the trail up to the Anasazi

Granaries at Nankoweap Creek.

|

As we settled down to eat our dinner, Rob Pitagora came over and handed my

lost hearing aid to me. It had been found in the water in the bottom of one

of the boats, and was about to be discarded as a piece of trash (it's a

tiney, in-the-ear model) when Rob recognized it and saved it for me. That's

almost as good as the saga of the ring on our trip with Dories in 1997.

Still more amazing is the fact that once it thoroughly dried out it started

working again, and it is still working. I have had it checked by Dr. Larry

Byals, my hearing aid specialist, and it is just fine.

After dinner we sat around, talking, joking, and reminiscing. We were

becoming more and more relaxed with each other each day, and these evening

bull sessions were developing into a very enjoyable part of the trip.

|

Our Group is, from left: Jennifer & Bill Huggins, Bob Groves, (standing)Phil,

Larry and Kevin Roberts.

|

During the night, at 10:10 pm by my watch, there was a meteor or some object

that shot through the sky from roughly South to North that was so bright that

it lit up the camp at least as brightly as a flash of lightning. I have

never seen such a bright object shoot across the sky. All of the campers who

were awake at that time saw it, so I know that it was not my imagination. I

have heard nothing about it on the news since we have returned home. I guess

that it was a much larger than usual meteor. The effect was beautiful and

dramatic. I will always remember it.

|