|

DAY 4. WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 14, 2002

Another delicious breakfast awaited us this morning. The fragrance of coffee

woke us up at 6:45. After stirring around, greeting each other over steaming

coffee, getting packed and ready for pancakes and juice we settled down to

our early morning routine quite easily. By 7:45 we were fed, boarded and

underway.

Our passage this morning was mild as far as the rapids and the turbulence of

the river were concerned, but it is a region that is packed full of geology

and history.

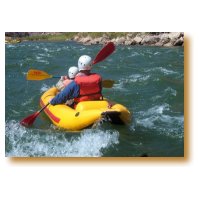

While we rowed easily down long stretches of calm water to Kwagunt Creek and

Rapids and then on to 60 Mile Creek and Rapid there was plenty of time for

Kevin and Larry Roberts and several of the Shers to demonstrate their skills

in handling the two inflatable Kayaks. Passage through the rapids at

Kwagunt, a 7-foot drop rated 6, and 60 Mile, rated 4, provided us with some

excitement. However all kayakers passed through unhurt, though there were a

few dunkings. The Shers, young, athletic and agile, proved that it is

possible to right a capsized kayak, and hop back in with astonishing

alacrity; certainly faster than I could get my camera focused.

|

Kevin and Larry in Kayak

|

|

Picture of Larry in Kayak

|

Meanwhile just before Mile 60 we came upon the dark brown, coarse-grained

Tapeats Sandstone. It is the bottom layer of the Tonto group, and has been

given ages ranging from 545 to 550 million years. Some have said that it may

be as old as 1.7 billion years, (give or take a billion) depending on which

mineral and which decay rate one is measuring. These geological ages are not

as exact as one is sometimes lead to believe when reading material submitted

for nonprofessionals. The Tapeats is also the bottom most layer of Cambrian

Period which is the oldest period of the Paleozoic Era. In most areas of the

Grand Canyon the Tapeats lies directly on top of the almost black,

metamorphic Vishnu Schist. The line between the Tapeats Sandstone and the

Vishnu Schist, two very different geological formations, is called "The Great

Unconformity." The absence of rock layers here represents a vast period of

time when the forces of winds, earthquakes and water completely eroded away

all of the sedimentary layers that should be there. The Great Unconformity

separates the Paleozoic Era represented by the layers through which we have

been descending and the Proterozoic Era into which we entered at Mile 60.

IThough it is not immediately obvious to our untrained eyes, it is in this

area that the so-called Grand Canyon Supergroup rises to river level. At

least some of the layers of the Supergroup become visible here. Most are

buried deep in the earth, thousands of feet down.

The obviously tilted layers of this group become more evident shortly beyond

Mile 60. They represent several layers of sandstone, limestone, shale,

quartzite and conglomerates, some of which are separated from each other by

relatively minor unconformities. J. W. Powell recognized these layers as

being a group separate from the Paleozoic Layers above, and belonging to the

Proterozoic Era. He noted fossils of stromatolites, the oldest living forms

discovered in the Canyon, in the Galeros and the Kwagunt Formations. I didn't

see anything that I could identify as these layers, nor did I identify the

coarse grained Nankoweap Formation above. I am impressed that Powell, who

was harried by food shortages, loss of oars, and a growing shortage of

clothing and blankets and all the stresses of running rapids he considered

safe, and lining his boats around others, was able to take time to study the

geology of the canyon sufficiently to identify these features. For all of

the faults that he may have had, he was truly an amazing man. I didn't see

the formations of rock he described around Mile 60; however, down below the

Little Colorado River the massive hills and slopes of orange and red Dox

Formation stand out as the most obvious feature of the great bend in the

Colorado as it swings around to the west. All of us could easily see this.

The Dox is composed of loosely compacted sandstone interbedded with soft

shale, and is easily eroded creating the broad sweeping slopes that were used

by the ancient Anasazi for gardens of corn, squash and beans. By the way,

back in 1914 Levi Noble named this formation for the voluptuous, red-haired

Virginia Dox of Cincinnati, Ohio. She was the first female visitor guided

into the Canyon by William W. Bass in the Western Grand Canyon. I guess Dr.

Noble thought the color of the Dox Sandstone reminded him of the color of her

hair. Something about her certainly impressed him.

Before we came to the big bend in the river we came to the junction of the

Little Colorado. It was flowing in from the left, clear and blue, more blue

than the Colorado because of its mineral content, and it looked inviting.

Five years ago it had been high, swift, muddy and ugly. We were unable to

even think about swimming in it. This time I was hoping to have an

opportunity to enjoy it, to go upstream to view its canyon, to swim in its

waters and to once again visit the cabin of the 1890s miner, Ben Beamer, on

the south bank, but we were allowed time enough only for a pit stop. Too bad.

Cruising on down the Colorado we watched the blending of the waters of the

Little Colorado as we glided by the island on which we had seen a coyote when

we cam this way on our first OAR trip back in 1993. Several of the most

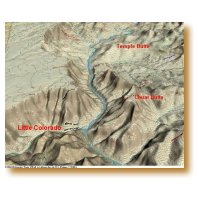

famous, or infamous, landmarks of the entire Grand Canyon lie just a little

way downstream from the here. They are Chuar and Temple Buttes and Crash

Canyon.

|

Map showing Chuar and Temple Buttes and Crash Canyon.

This is the site of the great June 1956 airline disaster.

Relief map with permission from Durango Bill.

|

It was on these two buttes and the intervening canyon that the two

airliners, a TWA Superconstellation and a United Airlines DC-7 crashed after

colliding with each other high over the Painted Desert on a clear day in June

of 1956. 128 people died in that disaster.

After a lot of bureaucratic foot dragging by the CAA (Civil Aeronautics

Authority - the predecessor of the FAA) and others, "…a series of crashes in

1958 finally led President Eisenhower to instigate a study into the nation's

aviation system. This committee recommended the design of a common air

traffic control system that would serve the needs of both military and

civilian aircraft, and the ultimate formation of an independent agency to

take over the functions of the CAA and to oversee this system. This agency

would become the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA)." (From www.web.mit.edu)

No other large, commercial airliners have crashed in the Grand Canyon area;

however disasters involving aircraft are not uncommon. The below the rim

collision of a helicopter (owned by Papillon Helicopters) with a sightseeing

airplane in 1986 killed 20 passengers on the plane and 5 in the helicopter.

On September 2, 1995 a corporate plane carrying the president and three other

employees of Adventure Airlines as well as 4 officials of the Japan Travel

Bureau developed engine trouble, and crashed two miles short of the Mesquitte

airport while attempting an emergency landing. All 8 were killed. A Papillon

owned helicopter crashed south of the Grand Canyon in April 1999, killing the

pilot and injuring a passenger. A single engine plane crashed about 2 miles

from the Grand Canyon Airport, August 4, 1999, killing two people and

injuring one. Another Papillon owned helicopter, based in Las Vegas, crashed

into the Grand Wash Cliffs in August 2001, killing the pilot, 5 members of a

New York family and burning 80% of the body of a sixth. Another Papillon

owned helicopter crashed on May 29, 2002, injuring the pilot who was the only

person on board at the time.

In defense of Papillon I should mention that since the midair collision of

1986 Papillon Helicopters has flown more than 700,000 flights, carrying 5.3

million tourists and had only 7 fatal accidents. President Steve Bassett

points out that this represents a more than 99.999 percent safety record.

When you take into consideration the fact that about 750,000 tourists take

about 50,000 flights over the park each year it is not surprising that

accidents occur now and then.

Some of us who advocate the prohibition of flights over the Grand Canyon

altogether, except of emergency purposes, site the statistics of injuries and

death to bolster our arguments, though the chief argument is the preservation

of solitude. Decisions of this nature usually follow money. Since tourist

flights are responsible for a 100 million dollar a year industry, one can

see that the completely banning of flights over the Canyon is not likely to

happen.

I'd like to make one more comment about flights over the Grand Canyon. In

1997, long after flights below the rim were outlawed, Bill Huggins and I took

Matthew on a helicopter ride as part of his Grand Canyon adventure. Our

flight took us from the Grand Canyon Airport at Tusayan across to the eastern

Canyon, over the mouth of the Little Colorado, up to and up Nankoweap Canyon,

then west to Crystal Creek and finally down its canyon where we again crossed

the Colorado to fly back to Tusayan. Even though flights below the rim were

outlawed at the time, it was perfectly obvious that we were several hundred

feet below the rim as we flew down Crystal Creek. I feel sure that ours was

not the only flight during which that happened.

Now back to our raft trip.

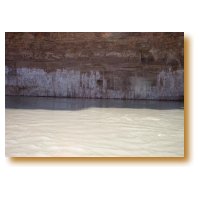

Two miles below the mouth of the Little Colorado we noticed the white,

crystalline deposits of salt on the east side of the Canyon wall. Eons ago,

when this area had been part of a shallow sea, evaporation had taken place

leaving a layer of salt deposited on the old sea bed, much like what is

happening in the Dead Sea and the Great Salt Lake today.

As with all of the visible canyon layers, after the uplifting of the Colorado

Plateau had taken place, followed by the down cutting of the river this

particular layer was exposed.

The Hopi Indians still come down the Little Colorado on their sacred "Salt

Trail" to these "Sacred Salt Mines" where they collect salt. Being sacred to

the Hopis these areas are off limits to tourists traveling by them on their

way down the canyon.

|

Hopi Salt Mines - Salt deposits on the wall of the Canyon.

|

About the same time that we were viewing the Sacred Hopi Salt Mines we

entered the first layers of the Dox Formation. This quickly became the most

obvious deposit of the canyon. Kevin and Larry continued paddling along in

their kayak, while members of the Sher family swapped off paddling the other

one.

Across the river from the Salt Mines the massive structure of Temple Butte

was easily seen. When Colin Fletcher, "The Man Who Walked Through Time,"

passed this way in 1960, the wrecks of 1956 had not yet been removed. He and

his friend, Doug Powell, a distant relative of John Wesley Powell, noticed, "…

the wreckage of both planes. They lay on the far side of the Colorado. All we

could see of them was a single section of fuselage perched precariously on

the brink of a two thousand foot cliff. The other plane seemed to have

crashed in a shallow side canyon, two hundred feet above the river. We could

see, strewn across the bare and silent rock, a swathe of small, gleaming

fragments. None of them looked larger than a child's coffin." Scotty tells

me that even now, 46 years later, hikers occasionally find small pieces of

metal in this region.

When we came down this way with Dories in 1997 we stopped for lunch on the

beach at Carbon Creek, whose canyon has been given the unofficial name of

"Crash Canyon." On this trip we did not stop there for lunch. As a matter

of fact I can't remember which beach we used for lunch, but it was somewhere

in this area. What I remember is that it was hot. We were getting close to

"Furnace Flats," the section between Tanner and Unkar Rapids, where the

summer temperatures have been recorded at well over 120 degrees.

The kayakers made it through the four foot drop of Chuar Rapids at Lava

Canyon, and were becoming quite accomplished. However, Rob and Scotty let us

know that we were now approaching the big, twenty foot drop of Tanner Rapids,

and it was time to bring the kayaks in. The rest of the trip down to our

campsite just above Unkar Rapid across the river from the Hilltop Ruins was

uneventful, even though we had some thrilling and wet moments in Tanner.

While waiting for dinner to be served, some of us sat around camp and sipped

our snake repellent, (1 part Beef Eaters to 4 parts ginger ale, or whatever

we could find) and some of us took a brief hike up to Anasazi Ruins on our

side of the river. The broad relatively level slopes of the Dox Formation in

Furnace Flats (level being a relative term in the Canyon) provided the

Anasazi many areas in which to plant their crops. Apparently changes in

weather patterns with a decrease in rainfall forced them out of their canyon

homes around eleven hundred ACE. (AD to those of you who went to school back

in the dark ages like I did.)

During the calm of the evening after dinner we sat around camp, reminiscing

about our experiences and generally enjoying our camaraderie.

|

Bob and Phil enjoy a quiet conversation after dinner.

|

Tomorrow would be our last day on the river. Sad.

|